Founded in 2005, Translit is a literary-critical anthology, publishing outfit and community of artists, poets, philosophers and humanities scholars. The editors of the anthology aim to bring forward various fields of confrontation in contemporary literary theory and the literary process. The first issue was devoted to the gender framework of poetry; the second to the “role of personality” in poetics; the third to the forms and features of the co-production of texts and reality; the fourth sought to investigate the forms of contemporary poetry’s social being in the context of its (poetry’s) secularization. The fifth issue asked the question, “Who is speaking?”, which nowadays implies a mapping of the intra-poetic (narratological) registers of speech production, as well as inevitably necessitating an investigation into the interrelationship of the speaking subject with instantiations of language and ideology. The following double issue (6/7) was devoted to investigation into the contingencies and obstacles involved in a transition from the rejection of the non-aesthetic (“everyday life”, byt) towards the active appropriation of this non-classical material. This process assumes a reassessment of aesthetic methods and is to a certain extent capable of leading to the transformation of art’s social functions as well. The latest, eighth issue of Translit presents an attempt to view literature as anthropological experience, cultural institution and social practice. The authors emphasize that they are primarily interested in the “transition from the investigation of literary facts belonging to an aesthetic series, to the analysis of the interactions between series and, first and foremost, between art and the socially political context”.

Translit has published texts by authors including the writers Anton Ochirov, Roman Osminkin, Kirill Medvedev, Aleksandr Skidan, Valery Nugatov, Andrei Rodionov, Andrei Sen-Senkov, Dmitry Golynko-Volfson, Marianna Geide, Alla Gorbunova, Maria Stepanova, Gali-Dana Zinger, Daria Sukhovei and Evgeny Rits; the philosophers Keti Chukhrov and Aleksandr Smuliansky; and the scholars Pierre Bourdieu, Jean Ray, Tatiana Venediktova, Igor Chubarov, Ilya Kalinin and Sergei Ermakov

In december 2013 - January 2014 was prepared #14 [Translit]

Pragmatics and Literature

Pragmatics and Literature

Just as in ordinary language a certain number of assertions constitute the completion of an action in addition to the act of utterance, so many literary techniques aspire to the status of phenomena valuable in and of themselves, beyond mere representation (cf. Mayakovsky, “To write not about war, but to write by and through war”). These phenomena not only carry significant illocutionary force, but often an entirely palpable perlocutionary effect as well (cf. Kharms, “Poems should be written in such a way that if you throw a poem at a window, the glass will break”). The subject who makes a performative assertion is assumed to have a specific kind of authority and to make the assertion in a specific situation; in just the same way, the poet is the product of the specific authority of poetic utterance and is more than sensitive to the situation, not being ceaselessly and tacitly a poet (Pushkin, “And among the inconsequential children of this earth/Perhaps he is more inconsequential than all the rest./But when the Divine word/does reach his keen ears…”). Twentieth-century analytic philosophy realized that one can “do things with words,” while the “poets’s words” have long been intuitively equated to “his/her deeds” without any sort of theoretical underpinnings.

What is traditionally understood as “pragmatics” in linguistics and analytic philosophy — the view of the utterance as “successful” or “unsuccessful” (instead of the category of “truthfulness” or “falsity” in relation to facts and the internal consistency of the utterance) — was also at one time scandalous. The functions of language have been correlated to literature through hermeneutics and structuralism, but never through the pragmatic philosophy of language. An investigation of the pragmatics of the literary utterance (similar to linguistic’s turn toward pragmatics and away from semantics and syntax) should refuse to examine the correspondence between the “depicted” and “extraliterary” worlds and also reject obsessive intertextual neuroses, in order to focus on the act, the gesture, the move made by means of the literary utterance and the realization of the text in a concrete situation. It should also address the question of what position the utterance occupies within the space of literature and in relation to other such manifestations, as well as what effect it seeks to have beyond the borders of that space.

Traditionally, literary theory concerned itself with what is actually said in literature; meanwhile, the analysis of illocutionary meaning (what action is carried out in the word) and particularly perlocutionary effect (what kind of effect is had), including in the broader (social) sense, usually boiled down to just bringing in confused biographical material or sociological constants. Because of this disregard of the rhetorical aspects of language, “pure literary value” conflicted with or was randomly connected to “usefulness”/ “practical value” — educational, didactic or directly utilitarian — but was never understood as action or as something in and of itself directed toward concrete effect.

We find another predecessor of the pragmatic viewpoint, one focused even more on literature, in the so-called “Bakhtin circle” (Voloshinov, Yakubinsky, Medvedev), with its “metalinguistics” project.

Unlike the Oxford school of analytic philosophy, here the utterance is not equated to the isolated speech act, which is initiated by an autonomous subject. Instead, it always discovers in itself traces of the views or words of some other — it is fraught, if you will, with the dialogic. Likewise, literary invention appears in response to another (preceding) invention, usually in order to challenge it. This reveals its immersion in a completely polemical context, in the perspective both of art history and its present organization. The pragmatic gesture is directed toward preceding modes of operation in literature and simultaneously seeks to overtake contemporaries and address itself to a newly invented audience.

Historical pragmatics and co-situational pragmatics. Since it is neither a calculable cell of genre morphology nor the product of an individual creative will, the event of the literary utterance directs the pragmatic task in both the diachronic redetermination of the generic system, and in the more localized co-situation of the poetic utterance. However, like the word in the metalinguistic project, the literary work is less a natural extension of the author’s body than something strung on pragmatic threads pulled between significant precedents of the utterance. Without taking these directed and oppositional qualities into account, it is basically impossible to identify the orientation of the literary work, to understand the text as an utterance (speech act).

Bakhtin stipulates more than once that the utterance, which is directed not so much at its own subject as toward others’ speech about it, constitutes a unit of scientific and artistic communication as well as ordinary and everyday communication (the former being stable forms of speech genres, mediated by social activity). Poststructuralist reception of Bakhtin’s theory reduced these discursive interactions to the textual (in which utterances neutralize each other in the shared synchronic card-catalogue, although written responses to other texts are obviously not the same as speech acts responding to other speech acts). With the pragmatics of the artistic utterance, the accent must be shifted from the reference to the gesture made by the speaker (Bakhtin’s circle affirmed the “cultural” (ideological) as something equal to the signifier, given in actions). Here the library metaphor has to be replaced by a theatrical one.

Thus pragmatics is yet another artistic and methodological move toward an externalized understanding of the artistic utterance (not the text itself, but the conditions and circumstances of its realization, included in the course of its production).

Just as meaning in language is only the potential for meaning in a specific context, literary facts are something fabricated in practice (something obscured by such writing pragmatics as the address to “eternity”), and the meaning of a literary work is its actual mode of operation and the revealed response. Finally, the analytic formula “meaning as use” correlates directly with Genette’s conditionalist criterion of literariness. This means that even one and the same literary technique can in different situations appear as different pragmatics of the utterance (the ascetic style as a consequence of depletion of the rhetorical tradition, as in Robbe-Grillet, or as a stake in the radical transformation of social communication, as in Literature of the Fact).

In this way, pragmatics is not the “what?” or even the “how?” of literature, but “how does it work?” (including in the sense of “how powerfully?”). With the turn to the practical, we are inevitably confronted with materiality. Institutions and communities, tools and technologies will also play a role. We can see the effect on literary pragmatics that comes out of media conditions (the difference between poetic utterances in a poem written for a private album vs. for mass publication), but we should not forget about the potential for poetic actions’ figurality, which lets us examine the “suicidal quality” of Mandelstam’s poems, or texts written in prison, as speech acts made in a specific autonomous way.

Sociology re-conceptualized things as independent reality — not merely passively signifying, but also actively acting — by anatomizing the mechanics of scientific discovery. Meanwhile, the actor-network approach to literary scholarship can demonstrate how — and with the help of which technical-rhetorical and institutional-organizational efforts — “literary discoveries” are achieved and what material and figural qualities of the sign were employed as agents in the production of literary facts.

In other words, if we understand pragmatics as a disciplinary lens (not yet a mode of operation inherent in literature itself1), then it demonstrates a fairly synthetic method, one that takes into account the logic of symbolic capital, purely textual devices for the production of meaning, the analysis of technique and the dimensions of the individual author’s accomplishment. Pragmatics is not a revision of the schoolroom question “what was the author trying to say here?”; rather, it is an attempt to grasp what act of utterance (l’énonciation) the author is actually making, at times despite that which is said (énoncé), and what gesture is being made in writing [A. Smuliansky, “The utterance as action and as act”]. The author’s individual intention is not important (likewise his/her explicit declarations regarding this intention). Instead, what is significant is the totality of conditions of the given literary-political situation and the given audience (including the social distance between them) that determined the construction of the utterance, as well as precisely how the writing itself completes the given action.

The task of pragmatics is not to lock texts into the economic statistics of the publishing industry, but to see in them the chess-game logic in which only those things are valuable whose modes of operation are different from the others [I. Kravchuk, “The novel as social gesture: preliminary notes toward a pragmatics of early Dostoevsky”]. That which is impossible to discuss in economic terms should be examined from the point of view of wordplay on the social scale. When the class position of the artist is no longer considered relevant (because of the reshuffling of class logic itself), there still remain various moves to be made in the social space of literature and epistemological bets to be placed [D. Bresler / A. Dmitrenko, “Throwing life-giving “seeds”: the pragmatics of repeated use of verbal raw material in Vaginov’s notebooks”].

The situation today in art is such that it is no longer possible to determine “what is art” according to purely external features — one and the same action might be art or not art. Precisely for this reason, we are usually interested in art which, as a consequence of external conditions, conceals a certain epistemological schism within itself: for instance, art that denies the existence of construction and completely dedicates itself to the material, but meanwhile has systematic and obvious recourse to the deformational features of language and/or sophisticated rhetorical resources. Or cases in which art insists on one thing (the object) while deriving its whole effect from something else (the visual) [P. Arsenev, “Literature of Emergency State”].

Regardless the mass of communicative-utilitarian terminology when talking about pragmatics, our attention to the topic is not an attempt to call for or to shove literature into some kind of suspicious “effectiveness,” but rather to discover those actions that literature itself “does with words” [I. Gulin/N. Baitov, “How to do things with the reader using words”]. Just as linguistic meaning emerges in the world of human activity in connection with the aims and interests of speakers, in literature the “world of action” is not opposed to any construction, but rather makes possible its creation.

Where we find (artistic) utterances, we also find relationships (including social ones). How literature imagines them, what kind of action it feels it should take within them or with them — is this action in the more metaphorical cognitive sense, or the social-externalized performative sense? How does the appearance of these relationships and the selected mode of action enter into the actual procedure of writing (it would seem, something that has remained unchanged over the centuries)? What happens with the pen — is it really equal to the sword, or does it get transfixed by the whiteness of the paper?

In another sense, we are also interested in the modes of operation within literature that are characterized by calls for simplicity of language. What is the real pragmatics of texts that ask to be called “simple,” “folk” or appeal to such values [P. Seriot, “The people’s language”]? How do they conceptualize themselves? Should they use language like that of Roland Barthes’ “woodcutter,” or have recourse to more sophisticated attempts to “escape language” and the mediation of the sign [A. Montlevich, “Fact as fetish: instead of a name”]? In other words, what myths and models of its own language are created by this kind of literature?

There is an even simpler case of this passion combining with real participation in politics (liberation- or oppression-oriented). When authors lay out their pragmatics, having completely identified themselves with one or another political force

[N. Azarova, “On the addressee, discursive boundaries and Subcomandante Marcos”], can we always suspect this pragmatics of antisemiotism? But what is the pragmatics of those texts that do not seem to be totally ignorant of the demands of politics and do not oppose them openly, but simultaneously select that type of “politicization” that flourishes far from the noise of the streets [T. Nikishina, “Discourse in the perspective of ecriture”]?

How, then, is pragmatics connected with politics overall — the most immediate, public and civic politics, as well as that of literature itself (but still — politics as struggle)? And what is the connection between these two kinds of politics and literature’s own connection with that which brings it into action and which actions it brings itself to (is the strong civic tradition connected with the strong national institution of literature?) [J. Rancière, “Mute speech”]?

The translation of Rancière analyzes the classical description of literature’s mode of operation as “the expression of the Zeitgeist,” like any other linking of the “work with the necessity of which it is the expression.” The chapter from Mute speech given here addresses this particular remnant of literature’s participation in a certain processuality/duration, including in the sense that “the object of its examination is something distinct from poetics — the external relation of literary works to institutions and morals, rather than their value.”

Art that understands itself as consequence and art that understands itself as cause. Is there more pragmatics in one or is the pragmatics just different in both cases (is it measured quantitatively or qualitatively1)? For instance, what happens with the writing methods themselves or with a pre-determined understanding of them in the case of texts “written in blood”? What happens to the supposedly independent object when it reveals traces of participation in one or another communicative game [N. Mironov et al., “Texts which cannot be judged by ‘purely aesthetic criteria’”]?

In the final account, pragmatics sort of leaps away from method (methods of examining literature) to the practice of literature itself (the viewpoint infects the doing), and thus it is impossible to establish a precise borderline between the viewpoint and the object.

Proceeding from all the above, this issue of Translit forces us into repeating a phrase very familiar in the humanities context: “this is more of an attempt to pose the right questions than to give answers,” which also goes for the “dialogic” quality of the materials included: collective authorship, interviews, polls. Furthermore, the issue includes illustrations from a Samara-based project involving artists and architects. The illustrations present functional models of various poetics: the poetic machines of the Lianozovo school, metarealism, conceptualism, direct utterance and the new epic come equipped — instead of manual instructions from the producer — with the reflected vision of a geographical and professional other, reported speech that penetrates and mixes with the machinery of these poetic languages [A. Ulanov, “Working models of poetic festivities”].

Notes

1. Furthermore, one could voice the reservation that not all literary works are characterized by equally obvious pragmatics; but the Formal method was, after all, more appropriate to some texts than others.

Translated by Ainsley Morse

Poetry selections (Translit 14)

1. Galina Rymbu

* * *

the all-elucidating blood of animals

politics: animals in a hut deciding how to be

a breeze in the hair of darkskinned animals

the belly cries of white elephants

moving within economic systems,

shedding skin, dropping fur

the critique of pure reason cleft by claw

sex acts in the lagoon, dark liquid, sobs…

death on the knife-edge of memory

the old leader in a heated coffin carried through the Siberian steppe

darkblue doublets bear fragmentary traces of the hunt, the savage flowering of phonemes

sensual wounds on warm flesh in the muffled consciousness of a gadfly

in the cold winters we gathered on our own

phoned absent friends from the hut

created a forest of soviets, harems of regimes

and only one made it out alive

ethics: they want to eat

finishing in dead signs

2. Khamdam Zakirov

Sense of the world at 5.15, Finland time

Last night I slept waking constantly, or even didn't sleep at all,

taking note of the dawning outside the window that came with changes of pose.

I dreamed of Navalny in a small northern town,

he was walking around and asking passers-by:

“Hey man! How are things around here? Should we come immigrate?

It's OK, not that many of us will come: it is known that 40% of all Tajik men

live in Moscow, plus the same number of women, also children and old people,

and their president manages the Russian border guards, no one else left for him to order around.”

Afterwards I dreamed of some poet talking about weight loss and

the pointless kilometers he's covered, some musician on food preparation,

some litterateur on the changed image of the average Muscovite,

some journalist on closing the southern borders and opening the western ones,

or this old acquaintance of mine, once a hip poetess,

now writing articles blind with hatred,

newly a jew- and homo-phobe, having long since sniffed out who's who behind the scenes,

Orthodox protectress of the Muslims, bitter enemy of the gay liberals, lesbo blasphemers etc.,

and all the while a lioness of the scene, selling off her couture dresses worn once or twice

and swearing as she stumbles over a new-laid Sobyanin flagstone...

Then I woke up and repeated to myself over and over: you need to stop reading facebook,

you need to stop reading facebook, you need... You need to read,

it's better to ruin your eyes and brains with books, I said to myself, then sat down

to write all this down and entitle it “My Facebook newsfeed is replacing my dreams.”

But not you, my love, although you weren’t there.

3. Nikita Sungatov

* * *

realpolitik on the picture

and know that he who fell like ash to earth

slums awash in flames

who was so long oppressed

the quotes open the loss

pieces of earth knock against the concrete

he will stand taller than the great mountains

you take off your dress we go to the theater

catharsis was experienced there

given wings by bright hope

The moral:

together striding gladly forth,

together we sing in chorus, of course!

4. Kirill Adibekov

Karl-Marx-Allee (excerpt)

And life was real, it was summer, the tower, the clock on the tower, birds walked along the clock's orbit, conversations about parachutes, the park for culture and recreation. Moscow, other capitals, structures, herds in the fields, thoughts of war.

promenade along the embankment, opposite the south Moscow side,

the water in two, in three hours

through the islands and all enormous Moscow,

à pas lentes

Up along

Tverskaya with the crosses and banners –

a religious promenade, graced

with the goodwill of the sovereign.

Up along

Tverskaya – the clear air of a Sunday

morning /

the onerous rheumatism

of an alley in the very

center of the summer city.

Further – a railing, further –

a cathedral; a run along the boulevards, further on the river.

The horizontal line of water and red

brick.

[...]

Motionless, in squares – your canonical face of a Madonna.

Momentary forms. Silence. Laughter. A tall cold building. The hard

soft scent of firewood. 27, morning. Or the tenth, the pink light fading

above the arch, on

the steep wall

here there is only the horizontal line of river, the horizontal line of the bed, the vertical

line of the belltower, in the distance. Here there is only light

through unabashed blinds.

5. Gleb Simonov

***

the inevitable land of three

beyond the unnamed pass —

needing itself as little

as time,

in slow streams

waiting for a white clean wind

from windless places,

where

the three

not speaking to each another

sit at a distance

waiting

for their interpreters.

Translated by Ainsley Morse

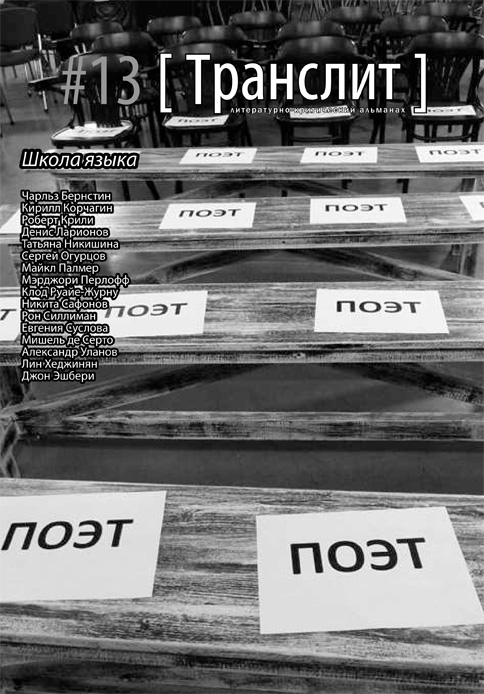

In may 2013 was published #13 [Translit]

The school of language

The school of language

What is poetry’s relationship to language? The question might seem rhetorical, but try to come up with even just two answers: you’ll quickly conclude that these answers will necessarily be mutually exclusive theories of the sign (as well as an economy of speech, a topology of language, a politics of the referent and the political economics of poetry as an institution). Thus any answer to this question is doomed to bear this rhetorical and plural character. You could say that poetry is never harmed by attention to (its) language, but at the same time many — from the naïve reader to the most sophisticated avant-garde programs — have sought in poetry a certain transitiveness, which to some extent contradicts the imperative of “being analytical” (existing for non-referentional writing)1.In any case, since it simultaneously constitutes the required nutrient medium and a great danger for poetry, this attention to language threatens to make poetry into an intellectual pursuit, excessively complicated and not at all “warm and fuzzy.” And this problem is directly relevant to a school of poetry that calls itself the Language School. But even so, language-centric poetry also represents a stance in the old dispute over craft vs. thought, which has long been hashing itself out in poetry and other art forms. And this language-centric line has always been linked to reflection (methodologically), to the essay form (generically), to theory (disciplinarily), and to the discourse community (institutionally). In this sense, we are dealing with poetry that is unequivocally and primarily avant-garde.

Like any avant-garde art form, the only thing this poetry does not question is questioning its own origins — material and media-based, social and ideological. Attention (which amounts to suspicion) to the medium in every sense, from the most corporeal (breath and voice, for Olson), including the traditional and therefore inconspicuous (paper, for Ogurtsov), and all the way to the electronic (new media, for Perloff). And under no circumstances should we forget about the (semiotic) micro-level of the medium: this poetry follows Mallarmé’s irrevocable imperative that “poetry is not written with ideas, but with words.” The Russian Formalists called it the self-containedness and self-sufficiency of the word; Bakhtin called it the word’s dialogic quality and heteroglossia; Lacan called it the approach to the symbolic (“everything that this word wishes to say comes down to the fact that it is nothing other than a word”): whatever the name, it is directed “against transparency, instrumentality and direct readability.” “Poetic language is not a window to look through, a transparent glass pointing to something outside itself, but a system of signs with its own semiological “interconnectedness.” To put it another way, “language is material and primary, and what’s experienced is the tension and relationship of letters and lettristic clusters, simultaneously struggling towards, yet refusing to become, significations.”2 And if it’s come to this (to being materialists), then we should acknowledge the thinking and production of poetry as dependent primarily on the medium (from semiotic to material) as the means of consolidating, preserving and exchanging signs. This materialism of the signifier makes Mallarmé and the Lettristes bigger Marxists than the apologists for vulgar sociology.

Poetry conceived spatially3 supposes that “the empirical experience of a grapheme replaces what the signifier in a word will always try to discharge: its signified and referent,” while poetry that reflects upon its own media-based origins extends to include investigations of poetic speech and experiments with it in new media (“for those ‘communolects’ now have everything to do with the one revolution that really has occurred in our own time — namely, the habitation of cyberspace”).4

But, as we have said, this is poetry wedded to theory. Not only the movement, but a whole journal carrying the proud name of language (L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E) brought together “contemporary ‘innovative’ poetry with the ‘new’ rapprochement between poetry and theory.” Like any rapprochement, this one provoked suspicion — that the fundamental task of demystifying “the referential fallacy of language” is more linguistic and philosophical than poetic, that this was experimental overkill whereby poetry would become a “bland cottage industry, designed for those whose intellect was not up to reading Barthes or Foucault or Kristeva.”5 A critique of the actual contemporary condition of poetry, yet one lying outside of “actual poetic tasks.” But what kind of essentialist definition can poetry have, if it’s still-poetry, and what is no-longer-poetry? Whether this is “poetry tortured by reflection” or released from that burden, nevertheless poetry “cannot be too far out of step with the other discourses — philosophical, political, cultural — of its time,” and will go on existing in this context. “The suture of poetry is removed from philosophy, leaving the poetry itself with a scar of theory: the ‘Century of Poets’ is superseded by the era of language” [S. Ogurtsov, “Besides bodies and languages”].

But still, what does the name of language poetry name? “‘Language poetry’ names the crisis of understanding language,” and this sets off a chain reaction touching on several neighboring theoretical areas.

One example is a topic very important for LS, translation — both between disciplinary languages and from one national language to another, such that the “summary area [of each language] expands out into uninvestigated territories” [E. Hocquard, “Blank spots”]. Perhaps we still consider the line in Russian poetry, “the mere mention [of which] thrust defenders of the ‘academy,’ observers of certain publications, protectors of ‘New Formalism’ or poetry of ‘the pine needle and home sweet home’ into paroxysms of idiosyncrasy,”6 to be a valuable link in the chain of translation, constituting a valuable cultural import — an agent of meaning absent and forgotten in the Russian-language universum. In the spring of 2013, however, a publication with incomprehensible texts and a majority of non-Russian names among its published authors can be identified as a “foreign agent,” pure and simple. This is why we decided not to limit the number of translated texts in this issue.

Among the transformations elicited by the crisis of the sign, of equal importance are those that impact reception. We see “a major alteration in textual roles: of the socially defined functions of writer and reader as the productive and consumptive poles respectively of a commodital axis,” while “the text becomes the communal space of a labour.” In step with the first avant-garde, LS puts perceptual responsibility on the receiver, thereby opposing art that mystifies by delivering a finished product. In this way “reading” becomes “an alternative or additional writing of the text.” But emancipating reception without taking on the attendant obligations in the collective production of meaning means that this emancipation can be misinterpreted: “any reading is a good reading.” However, one more rule stays on as a security guarantee: “read semiotically, not referentially.” Language understood après Marx and Wittgenstein forces us to discard “referentiality as a disorienting search for the pot at the end of the rainbow, the commodity or ideology that brings fulfillment.”7 Thus one of the main lessons to be learned from the “school of language” lies in the fact that the politics of utterance can lie beyond the referential plane, which ordinarily limits our understanding of the political in poetry.

This issue will inevitably conflict with the expectations of those who’ve grown used to understanding leftist poetry as a story about or call to revolution8. Language poetry is not about the intention to make the language of poetry complicated, so that “ordinary people” can’t understand it. It is rather an attempt to examine “ordinariness” or “naturalness” itself, as something that is organized and not very simple at all (one of these models can be found in Bernstein’s estranged retelling, “I look straight into my heart and write the exact words that come from within”)9. Supposedly opposed to “direct utterance,” this model can be of service to social communication as well. Yes, this is a rupture of lively communication as fraught with ideological transmission, but also rupture for the sake of restoration (of the conditions) of new communication — a transition from another kind of syntax to another kind of social relations, a new social syntax. This is a political critique of language developed in poetry.

“In experimental poetry, the aesthetic search is isomorphic to the social search” (L. Hejinian). As Marjorie Perloff notes in a critical response to the movement, LS “poetics had a strong political thrust: it was essentially a Marxist poetics that focused, in important ways, on issues of ideology and class.” A politics as old-school as they come, one that takes into account the linguistic procedures of political subjectivization (Althusser), but that has not yet dissolved “the universalism of critical leftist thought” into the practice of “particularist discourses of gender, race and nation,”10 and is moreover fertilized by good old Party-style self-criticism. At the same time, in some respects the politics of LS look entirely Foucauldian,11 hanging between the industrial and the post-industrial.

In any event, it’s time to move forward. Since even politics has now long been “not public, but mass-media-based” and “the very status of knowledge and thought in the new social-symbolic order remains unclarified,” we must now “rethink the function of language in the cognitive everyday, not denying the linguistic nature of our corpo-reality.” In his essay, Sergey Ogurtsov develops a media-based and institutional critique of poetry, in particular, (post-) language poetry itself (“Identifying itself with text, poetry simultaneously drops out of the generative procedure of art and finds itself dependent on the material fate of text as information medium,” and critical writing turns into creative writing). Only by analyzing the material foundations of poetry [R. Silliman, “Political economy of poetry”] is it possible to take poetic hubris down a peg, and to see poetry’s dependence on the non-reflexive forms of existence. Consequently, it becomes possible to annul the contract with fixed forms in order to save the name or essence itself of poetry (historical consciousness and conceptual thinking) — “to drag it out of its own fragments” (the linear writing with which poetry identifies itself) and readdress it to a different practice, which we could call the self-critical reconceptualization of truthfulness. The (old) politics gets criticized through language poetry, while the fixation on language gets criticized through a politics of truth.

To arrive at a full understanding of the “typically samizdat” experience of the avant-garde, we need to not only study its institutional organization in academic articles — we should also strive to regenerate its basic impulse by precisely duplicating its writing and self-organization in practice. Sometimes it can be productive to try to adapt a foreign past to our own present moment,12 to apply the direct experience of a community in “leading position” (literally, the avant-garde) to a developing community (as we can see in the dialogue between Natalia Fyodorova and Charles Bernstein). To a certain extent, this issue of [Translit] is not so much an exercise in literary historiography as in self-reflection and reconnaissance of our community. Regardless of the fact that it might seem subordinated to a very particular topic and its strangely amorphous title, this issue actually gathers together all of our recurring themes (language, media, the relationship between reality and writing, the author and the text, the sociology and anthropology of literature, the politics of utterance, theories of subjectivity and the community, the history of creative work understood through communism). But — again — we need to move forward.

“There exists no separate truth-procedure called “poetry” – there is only art.” The crisis of the media and institutions with which poetry-art was once identified allows us to rediscover “poetry” anew, but on new grounds. This is not necessarily a “transition to a Gesamtkunstwerk of the multimedia, not even rejection of text as such. <Instead, we uncover> an organization of the language of poetry on other foundations, which are connected to the new understanding of language in its subordination to the grammar of truths.” This grammar constantly modifies its structures according to models of non-linguistic language operations (first and foremost, those of visual art)” (S. Ogurtsov).

In light of these intersections, this issue of [Translit] is paired with a collective exhibition, which presents works that draw together discursive and figurative experiments (see the works of the participants on color pages). Undergoing its third birth, the avant-garde discovers its inborn traits: generic transgression and movement past the boundaries of the work, self-criticism of the medium and utopian overtones, transformation of the modality of participation and re-socialization. In this nearly predictable order, accent on the hermetic form gives way to inroads of social activism: after the battle is lost, the war with the dominant is continued, and activism returns to the abandoned laboratories of emancipation and begins working towards the next phase in the reinvention of its cognitive arsenal. One of the characteristic constellations of this moment is the rapprochement of the plastic and the rhetorical. The trajectories of art-instead-of-philosophy (a long-described phenomenon) and of poetry that pushes toward understanding itself spatially are finally at risk of intersecting. The bankruptcy of logocentrism forces the most sensitive of today’s “artists of the word” to come to terms with adjacent materials and techniques; meanwhile, visual art, which has long sought an acceptable code for self-description, can only be of service to the school of language.

1. “Poetry is more than the direct voicing of personal feeling and/or didactic statement…poetry, far from being transparent, demands re-reading rather than reading, [it is] News that Stays News.”

2. McCaffery, quoted in [M. Perloff, “After Language Poetry: Innovation and its theoretical discontents”]. See this issue.

3. “The poem is distributed across the page...” [K. Korchagin, “Distributed speech: extension and fractionality in Dragomoschenko poetry”].

4. M. Perloff.

5. “The feeling/intellect split had probably never been wider.” M. Perloff. All above quotes from McCaffery (SUP), quoted in M. Perloff.

6. A. Dragomoshchenko, “Slepok dvizheniia,” in NLO No. 113 (2012), http://magazines.russ.ru/nlo/2012/113/d33.html

7. All above quotes from McCaffery (SUP), quoted in M. Perloff.

8. Though even in these two options language begins to conduct itself differently, which fact ought to attract more attention than the referent, which remains unchanged.

9. Cf. Wittgenstein who refused to distinguish between ordinary and non-ordinary languages, considering “ordinary” to be sufficiently “strange”.

10. [S. Ogurtsov, “Besides bodies and tongues”]. Mullen speaks ironically of her dark-skinned fellow students, who asserted that while it was normal for white poets to reject “the voice,” for them it was not – since they had need of “their own subjectivity.”

11. In his 1981 essay “Constitution / Writing, Politics, Language, the Body,” Bruce Andrews describes politics as “a struggle for norms over the body,” and the politics of writing as “a politics of the body,” where “reason is a part of the body,” and “experience is always experience of the body.” Правильно ли я поняла «фукиански»?

12. The political essays of Michel de Certeau, written in the fall of 1968 and dedicated to the “acquisition of speech,” coincide to a surprising extent with the political intuitions and emotions in today’s Russia.

In November, 2012 was published Translit #12

The charm of the cliché

The charm of the cliché

Literary common sense warns us: the cliché is something to be got rid of. But the fact that we are being warned means that literature is a space within which the likelihood of clichés appearing is quite high, and the phrase “to get rid of” suggests that clichés are in some sense inevitable. We could say that literature lives by a suspiciously ineradicable logic of rejecting the cliché in the name of new invention. However, if throughout the whole long history of literature this distressing substance has never been successfully eliminated, it’s hard to believe that literature can get by entirely without commonplaces. Whether the situation was like this to begin with or became so as a result of extended opposition, literature needs clichés.

But literature likewise can’t get by without something other, that threatens its existence, calling us to remember that which is higher than words and that calls for their constant reassessment (if not rejection). The Formalists brought the first tidings of the systematic deterioration of the means of expression into Russian literature: even if the world does not change, the forms of its description in literature become automatized. But the main reason for the hatred of cliché lies less in the actual nature of the cliché (good or bad) than in the function it fulfils. And it’s a political hatred: entrenched forms of expression offer shelter for the consolidation of conservative ideas. Permanent revolution in style is provoked by the same thing as political revolution — the corruption of forms of representation. But if in literature this leads to the transformation of everything into commonplaces, in politics we have the equally chronic tardiness of socialization (language is easier to regulate than reality). Perhaps the reason for this asymmetry lies in the fact that words, unlike things, have no consumer value. But the wide circulation of clichés is suspicious in and of itself — it gives away the parasitic presence therein of ideology and mythology. Every clear instance of reasoning — every word used — conventional syntax1 — old grammar2 — patently obvious morphology — and, finally, the letters/sounds themselves3 — all of this works for the old order and can conceal cognitive and political clichés at any level, clichés that inhibit the free connection between words and objects [Jacques Ranciere, “The poet’s politics: the captive swallows of Osip Mandelstam”]4. In order for these two to meet freely and accidentally, a certain retardation of brisk communication is necessary; paradoxically, a belabored form — one nearing the refusal of language — is needed in order to force words to speak once again. The most radical method of struggling with cliché in this sense will naturally be silence (Rimbaud’s exit or Krzhizhanovsky’s “I am so much a poet that I write no poems”). However, this is precisely why these poets and their comrades are required to turn one last time to words — in order to designate their refusal of them. And it is here, at the point of a complete and ultimate taboo on expression, in this literary Auschwitz, that we find the starting point for collaborationism with cliché.

Thus, a no less forceful reason to declare emergency is the necessity to transmit that which in and of itself provokes the total annihilation of literature. If at one time stylistic clichés were gradually overcome under the aegis of the cult of form (all the way to its eventual dissociation), now — when that cult’s strategy itself is more and more often qualified as a commonplace5 — the main target has become the referential cliché. In this case the tactical compromise with conventionality of expression is provoked by the fact that misshapen reality itself calls to be described in forms minimally distorted by style: much material, little art [Taisia Laukkonen, “The modest charm of graphomania. On the literary strategy of Yuri Dubasov”]. Literature is written not about war (camps, blockades, etc.), but through war, because war no longer requires special artistic methods; staking its claim on reliability and documentary qualities, it establishes an emergency in literature and rescinds the latter’s constitutive and regulative rules. Authenticity and the ability to achieve the status of witness is understood here as a quantity in reverse proportion to the literary made-ness of a text. The author of such literature expresses his readiness to be anonymous, to be a nameless witness, a registrar, author of a protocol. Facts, numbers, and things are all equally of value insofar as they help the writer to forget what he is writing, as he hesitates between the role of medium and that of journalist [Vitaly Lekhtsier, “Types of poetic subjectivity and new media”].

In both cases, however, it seems that in the struggle with stylistic and referential commonplaces literature must make reference to the external, must go neurotic through exposure to political, social and existential horror, in order to acquire the right to pronounce a few more phrases about the impossibility of speaking. And for quite some time now — phrases specifically about the impossibility of speaking beautifully. All the more so when speaking of “Such a one”, which is made through the main justification of opening her mouth, from which had already issued so many monotonous cries of “wolf!” However, when literature stops playing this role too (having been reassured that it is enough “just to write”), it stops trusting itself. It’s enough to attend a session of the black and white magic by “its subsequent unmasking”, to see literature losing its strength.

Furthermore, in addition to the maniacal (graphomania) or enlightened (rhetoric) adherence to models, the insatiable desire to express “that which has never been” itself leads to the involuntary use of cliché [Dmitrii Bresler, “Konstantin Vaginov vs. “the incessantly disintegrating world”: to fight cliché using its own methods”]. So what is more dangerous: the inertia of language or the pressure of “content” that does not take into account and therefore stumbles all the more over that which has been? Which is the straighter path to cliché — inattention to the structure and genealogy (of literature) or to the signal calls of the spirit?

The very myth of the thought burdened every instant by language is rooted in the dualism of language and thinking, which has a respectable philosophical pedigree. Everything acquires its possibility only through mediation, through representation linguistic or political. Human expression is doomed to “supplement,” poetry is created from words, not ideas and so on. Although the majority of poets do their business with the ephemeral hope of overcoming language.

But that’s not the most interesting part. People always talk about certain discontiguous literatures, or to be more precise, about literature and that which is called to subvert it, i.e. the avant-garde.There exists a literature that is recognized and read as literature, and is therefore “just literature.” And there is a literature as yet unrecognized (autonomous? experimental? zaum?), which does not wish to be recognized as literature and serves as an orientation point for the horsemen of the Literary Apocalypse (and for “those-in-the-know”).

Thus the problem of the cliché is tossed over into the sociology of literature: in order to be original in literature, the bourgeois has merely to reject everything he was taught in school; but what can the people do who have nothing to forget besides their own clichés? [Aleksandr Smulianskii/Pavel Arsenev, “The canon that never became. A dialogue on literary (re)production and production literature”]. The argument for the socio-cultural relativity of the cliché makes it into a political term; ricocheting off the question of its nature, it shoots out questions about the nature of social divisions between those who culturally have something to push away (though the cliché is produced precisely in the pushing away), and those who have nothing to push away and for whom even the mastery of commonplaces is actually a support for thought.

In its uncompromising opposition to stock phrases (“they’re always used by the stupid ones!”), the avant-garde does not acknowledge that it makes use of that which it has itself made. The situation must be envisioned continually and at a distance: when some words already seem “empty” to one (let’s say, avant-garde) group, for others these words retain their strength and absolute authority. And precisely those words that proper society considers “grand”, capable of influencing individuals indifferent to the latest rhetorical contrivances (some of which include their visible absence). Thus occurs the great refusal to be comprehensible (to the majority).

In this way, the phenomenon of the cliché-stereotype-commonplace bifurcates: first of all, we always need to clarify the position from which we are talking about cliché — that of reader or writer (even in cases where the cliché gives the reader the pleasure of assuming that he too would write the same thing, while the writer can always be considered the first critic of his own cliché); and secondly, we have to understand that the cliché is an extraordinarily historical phenomenon — that which was yesterday a forbidden invention becomes a widespread device today, and hackneyed, spent material tomorrow (this is also constitutive for invention); third, diachrony multiplied by positionality gives the dislocation characteristic of all contemporary culture, which not only is flooded with commonplaces but within which we no longer understand the function of each individual commonplace — that of an unconscious imitation or a conscious distanced exposure [Pavel Arsenev/Igor Gulin, “The tragedy and farce of Soviet language (on the linguo-pragmatics of Gleb Panfilov’s films”)].

In any case, now in addition to being aware of the historicity of clichés (which are not born but come to be), we also know the very definition of cliché. In addition to periodicization we will bear in mind the multiplicity of perspectives or positions in relation to cliché: the naïve, the resisting, the enlightened, the meta-position.

When you try to avoid cliché, it only grows stronger. But if you chase after it, will it not try to save itself by running further away? Inviting cliché into works, art seems to do away with the neurosis of authenticity — but how this is done is important [Gleb Napreenko, “Art inside the machine”]: we see that the aestheticization of cliché follows from an overdose of high culture, not a deficit. The peculiar dandyism (like “the exceptional talent for decadence”) of reception and use stays tactfully silent about the most important aspect of commonplaces: if they allow to take such a different positions, they are no longer common.

The genres, rhymes and other literary conventions (hence stylizations) that have become commonplaces seem from the very beginning, having been discovered, to be doomed to move in a certain direction of generalization; every leap forward risked becoming (or hoped to become6) a well-trodden path. However, at some point there appeared a route that ran in the opposite direction, one that consists in displacing not the automatized form itself but merely the framework of its reception; placing it into a context so privileged that in it, the poverty of the form begins to look like an original solution: ready-made, camp (meta-kitsch), etc. The cliché has always been located in the eye of the beholder, but in this context it ceases to be a cataract.

There are various methods for placing a cliché in a strong (urgent) position: irony, accent, slight distortion, barely discernable shift, demotion. In this position the cliché cannot be ignored; the author not only knows what he is doing, but is also hinting to the reader (though again, only to the enlightened one) that “we are both here” on the same side of language [Alexei Yurchak, “Critical aesthetics in the period of imperial collapse: ‘Prigov’s method’ and ‘Kuryokhin’s method’”]. The form-made-difficult now acts in the guise of the automatised form. The reader, having already begun to feel at home with the “difficult” language of literature, is disappointed yet again: he is losing sight of the writer, not understanding whether the latter is so persistently using (meta-) clichés intentionally, or just repeating them without noticing. Clichés once again become the blind spots of language. A good contemporary example: aren’t memes a manifestation of this media-modification of the commonplace for those who are born into cliché and thereby condescendingly sympathetic (especially to those tired of avant-garde clichés of the dyr bul shchyl 7 variety)? [Maksim Aliukov, “The patriarch’s watch, or the meme as the illocutionary suicide of criticism”]

In the end, if the problem of the cliché was limited to literature, we could decide that it isn’t of such first-order importance and leave it to the arbiters of rhetoric. But from literature cliché leaps across into social speech, from the means of expression — into receptive reality [Pavel Arsenev on the “Red Storm”, “Revolution in the individual head”]. Every time a commonplace is (re)invented thanks to a useful observation, the militia shows up and starts spreading rumors about the extent to which it is widespread in “real life”: “If people saw a sunset like this in a painting, they’d say it was unrealistic.”

The constantly postponed unmasking of language and the immersion in pure “presence” is precisely what supports every ambition towards invention. The charm that we intend to probe in this issue is therefore connected less with calls for the clichéd (even if in fun) quality of language than it is with a summons to rethink the structure of contemporary literature as one sequestering cliché at its very center — and that therefore can be characterized by centrifugal movement [Antoine Compagnon, “Theory of the cliché”]. If at some point it could thought that with the help of literature people could think their way to truth or achieve perfection, today the central demand is for the most successful flight beyond the limits of such a program (which has become clichéd), as well as beyond any territory touched by the metastases of the commonplace. The cliché is precisely that which negatively determines contemporary literature, and therefore the use of cliché is an attempt not to continue the movement away from stale everyday language into heavenly pastures (themselves doomed to become that which will be scorned by future pariahs of the commonplace), but rather to figure things out once and for all — having plunged into the inferno of the engine of literary evolution, to figure out whether the cliché is an obstacle to elegance and expression.

1. [Anastasia Vekshina, “Rubbing cliché the wrong way: the physiologization of metaphor in Dostoevsky”]. P. 16.

2. [Evgeniia Suslova, “Tautology as de-phraseology of the cliché in the poetry of Vsevolod Nekrasov”]. P. 74.

3. Whose halfway-decomposition in the work of letterists marks the triumphant completion of this annihilation.

4. In this way, criticizing symbolist practice and the philosophy of language (including a certain amount of the philosophy of history and political practice), Mandelstam advocates the disconnection of words and things that have merged into symbols that are indistinguishable one from the other on both the conceptual and the corporeal levels.

5. Schopenhauer: “In essence, the first and only prerequisite for good style is that you have something to say”.

6. Baudelaire: “Creer un poncif, c’est le genie. Je dois creer un poncif.”

7. Aleksei Kruchenykh, a major poet of the early Russian avant-garde, opened his 1913 poem “In my own language” with these made-up words that emphasize the most guttural, cacophonous sounds of the Russian language.

Poems of the issue

Alexei Kolchev

pistol

I take out my pistol.

It’s already soaped.

A. Vvedensky

1

when I hear

the word

culture

I reach

for my pistol

the pistol plays

an important role

in contemporary

art

with a pistol

artists

paint paintings

with a pistol

poets

draw poems

musicians

pick out harmonies

on the pistol

cinematographers

with a pistol

shoot

successful

feature films

maybe

I too

can

with the help of a pistol

extract

something

from myself

2

when I hear

the word

pistol

I reach

for my pistol

when I hear

the word

woman

I reach

for my pistol

when I hear

the word

the word

I reach

for my pistol

plastic

combat

gas

traumatic

pneumatic

water

construction

when I reach

for my pistol

I hear

the word

where is my

black

word

where is my

black

woman

where is my

black pistol

* * *

She will not be defeated by my reason.

M. Lermontov

i’ve nowhere to put my weariness

like nowhere to put my eyes

while staring from the darkness

are watching other eyes

there’s the homeland there’s the birches

there’s the little house with chimney of brick

a pale-blue tracksuit lurches –

there rambles a little blurred hick

he’s russian? of course he’s russian

defeated by his fate

while far above the flattened plains

there sounds a mountainous retreat

Denis Beznosov

laws of the other

in and of itself a pencil sketch is exactly the same text only moulded from a different dough

this is probably how klossovski thought he had reasons to think in this way especially after the damage

done to the categories of human speech, the winking fabric of chromosomes which emerged instead of

the rotted-through constructions ankle-deep in sand the image replaces speaking rolling around on the floor generously

handing out prompts to all takers regardless the merits and shortcomings of the witnesses to the triumph

10.13

who crosses the street

who is growing a beard

having combed his hair who sat down

sits and reads the paper

theatre repertoires

the crime reports

who is losing a tooth

who is growing round

who calls his wife

the wife explains who

the rules for behaviour

in public

places

Vladimir Gorohov

(from Poems about music)

***

I respect black people.

The radio was

Playing black people again.

I was sitting again

Listening — way to go black people! —

Like nightingales they were

Trilling, those black people!

Naw, man — nightingales

Don’t even hold a candle

To black people, man.

I’d tear out my heart for black people.

I respect ‘em, man.

from Poems about poems

Poem

I started writing a poem, man.

And I wrote something, man –

Then I see — that’s not a poem, man,

That’s like some bullshit, man.

I tossed it. Started a new one.

Then I see — that’s not a poem either,

Some bullshit — started off sweet –

The poem won’t work.

Tossed that shit too, man.

Started a new poem.

Started off bad — tossed it, man –

Just some bullshit, not a poem.

Naw, probably it won’t work

Writing a poem right now.

Maybe something’ll work out later.

But for now — bullshit.

Poem.

(from Poems in foreign languages)

***

Dont bee effreid if iu hev teikin

Eh pees of peipa end eh pen!

Not yzee eez eh poem meikin

On menee faktorz eet dipendz.

Bat yf sam diffikalteez mitting

Iu hehvnot sei iu hani stop –

Vill eech attentiv bee yo rider

End hee vill neva sei iu nou!

In January, 2012 was published Translit #10-11

Soviet Literature

Soviet Literature

What has brought about our interest in things Soviet (or what, on the other hand, provoked the previous lack of interest)? Our confidence in the obvious fact that the so-called Soviet aesthetic (however that might be understood) was once dominant, while now certain other codes are dominant? That truth-value dimension of politics, which infiltrated all of Soviet culture (even when the former came into conflict with the latter)?

The central question of this double issue is posed in relation to the everyday reality, social sensibility, anthropology and culture of the Soviet era (or, dare we say, “society”?). Naturally, we are concerned here not only with literature. However, literature particularly as a social practice and political speech in general were allotted a special role in Soviet society; for this reason, the title of this issue (significantly expanded in its range of disciplines) nevertheless contains just this phrase. Of course, during the Soviet period there was no room for communication as such — even artistic — but there was still space for literature. Thus the diffuse concept of “Soviet literature” is not meant to exoticize its object, but rather to illuminate the extraordinarily mediated quality of the contemporary cultural consciousness itself. Indeed, what was the construction of the Soviet subject like back then, a construction that satisfied a hugely logocentric state of things? This is also an important question (examined in the article by Ilya Kalinin).

If we are to talk about literature according to the rules of traditional philology, what do we understand as Soviet — literature as “part of the overall proletarian cause,” “the pin and wheel” of one great united social-democratic mechanism, <…> a component part of organized, systematic, united social-democratic party work,” or as the entire field of belles-lettres, all of the texts that appeared throughout the existence of the Soviet Union? Where do we put émigré literature? And literature written by the various ethnic minorities of the USSR? How do we bring about the divorce and divide the property between Soviet and anti-Soviet (Aleksandr Zhitenev’s survey examines some of the most typical scenarios in the latter category)? Sooner or later, increased attention focused on the phenomenon of Soviet literature will necessitate a reassessment of the categorical apparatus of the contemporary humanities (see an attempt at this in the “Politicization of cultures” project).

It is impossible to imagine Soviet literature without this predicate, because it possesses a strikingly different function from that which is typically considered literature in its “normal aggregative state.” The literature created during the existence of the Soviet Union by people who were in one way or another connected with it turns out to be, like it or not, part of a large universalist project, rather than a one-time example of a purely literary project. Even in those cases when literature “has a place” not thanks to but rather despite “everything Soviet,” it still has as its (negative) source the need to relate, perhaps to critique (various things in various ways); but it is always located within the boundaries of a shared fate. These stipulations, however, should under no circumstances be understood as intending to excuse or justify anything. On the contrary, they serve to illustrate the situation in which Soviet literature must be not less but more than “just literature” (cf. “all the rest is literature”): whether literature that seeks to abolish the division of labor into literary and manual (see Ivan Kostin); literature that is created in several languages simultaneously and represents completely different classes of “the Soviet people,” but which is genuinely united by the struggle “for those values which, though distorted, crudely resisted or even turned inside out over the course of the Soviet project, nevertheless lay at its foundation” (see Sergei Zavialov’s review of a collection of wartime poetry); or, finally, literature that continues to search for realism in the non-censored literature of samizdat in the late Soviet years, even after this concept began to morph into a form of struggle with the latter (see Aleksandr Zhitenev). And since it quite quickly becomes clear that there was a discrete set of problems that tied together all of this “Soviet literature,” we ask: what is the function of the boundary between the so-called “official” and “non-censored” Soviet literatures, a boundary drawn by and still useful to, first and foremost, today’s new nomenclature (though they may not yet have completely defeated the old)? And as long as this struggle for definition continues (though none of the sides involved is unequivocally attractive), perhaps the most valuable thing now would be to figure out what Soviet literature represented as a general form, the various segments of which were part of “a struggle waged more between different Soviet sides — progressive and reactionary — than between Soviet and anti-Soviet.” Right now we need to be able to think about literature as a writing practice that goes outside the legitimate and comfortable bounds of the literary salon.

We can extend this logic to the culture as a whole, in which “socialism establishes itself not only in the iconography, in the images that embody the ‘communist party’ and its leaders: its elements are scattered throughout the entire living space of the ‘Soviet.’ This means that a critique of the “socialist” or “communist” cannot be reduced to the traditional division between official (false-socialist) and unofficial culture, or to that between official and depoliticized everyday reality. The Soviet past certainly contains an enormous number of examples of false socialism, of petit-bourgeois Philistinism. But at the same time there are also isolated, unrepresented spaces of voluntary, non-ideological socialism — non-ideological everyday spaces filled with a utopian faith that cannot be reduced to the declarative slogans of socialist realism. These spaces have not yet been studied at all” (Keti Chukhrov).

And yet, those who “have actually experienced life under socialism” will perceive this interest in the Soviet theme with the typical calculated perplexity and condescension otherwise directed towards young writers. In our view, however, the absence of this (usually traumatic) experience creates an investigative point of view much less subject to ideological appropriation, and artistic efforts more open to new experience.

This new experience of the return of history is imminent, as is, consequently, an importunate demand for the identification and criticism of ideology. The current issue of Translit was slated to come out at the end of last year, but December 2011 ended up being marked by developments of an importance that compelled everyone to relate differently to their “ordinary activities.” The question of rapprochement between serious theoretical work and contemporary social practice was once again raised. Thus, certain texts that might have seemed abstract historico-archival investigations actually turned out to be relevant not only in the so-called academic context, but also for entirely of-the-moment debates about contemporary institutions of political representation (see Ilya Kalinin).

Many of the pieces in this issue, which focus on the synchronic transformation of stylistic and phenomenological perspectives in poetry (Aleksei Kosykh, Pavel Arsenev), the ethics and economy of creative labor (Veronika Berkutova), medial analysis of cultural practice (Mikhail Gronas lecture synopsis), the social dynamics of the privileges of writerhood and the circulation of the authority of the public utterance (Mikhail Nemtsev), seek to avoid the limitations of the ordinary philological repertoire of methods and conclusions — hoping to break out into the realm of real contemporary issues.

We were equally concerned to track the influence of the “Soviet” not only in literary material, but also in film (Andrei Fomenko; Andrei Gornykh), in the organization of labor (in interpretative practice — Richard Stites) and other areas. In terms of questions of creative labor and the traces of the Soviet presence still present today, one of the most reflexive fields of inquiry lies in contemporary art; this issue features several textual-visual contributions towards this topic (see Khudrada, Arsenii Zhilyaev).

Along with the publication of excerpts from a book by Oleg Kireev devoted entirely to the literary and historical situation in the 1950s, we also sought to take a close look at today’s literary situation, how it is transforming and generating contemporary cultural activism. The experience of former Soviet republics, located on the far side of the post-colonial barricades, is particularly valuable here (see Anastasia Vekshina, Sergei Zhadan, Giorgi Khasaia an others). And especially among those who — mainly for age-related reasons — are not repulsed by Marxist aesthetics or theory, nor burdened by the complex of belonging to an “excluded culture.” This is also important because elements of the Soviet cultural consciousness have become displaced in culture and history.

The tendency towards the “falsification of (literary) history” has only recently become obvious: “the aspiration to write oneself into an idealized pre-revolutionary tradition betrays the desire, typical of the 1990s, to erase the still very relevant Soviet past from the collective consciousness” (Kirill Medvedev). At the same time, the danger looms large of a revanchist interpretation of Soviet culture, which would be most obviously demonstrated in a prohibition on the institution of new utopian projections. In the final account, only a complete rethinking (and not one or another revaluation) of the Soviet experience will allow us to formulate a liberation agenda for today, to clarify to what extent the model of class struggle for cultural hegemony is still appropriate in today’s circumstances of cognitive capitalism and the rapidly changing composition of society.

In the first article of the issue, “Early Productivism and the critique of ideology”, Ivan Kostin examines the polemics carried on from 1918-1921 between the theoreticians of “productive” art O. Brik and N. Punin and Narkompros leader A. Lunacharsky. The main issue was the ideological role of art, which the Productivist theoreticians denied and Lunacharsky affirmed. The Productivists’ critique of easel-painting, from our point of view, duplicates Marx’s critique of ideology, while Lunacharsky’s position is based on the pragmatic logic of state propaganda. This lack of understanding in a situation of state monopoly on artistic commissions led to a decrease in the role of innovative, “leftist” art in Soviet culture and ultimately made its full realisation impossible. Nevertheless, the study of Productivism as a project and, by extension, deeper knowledge about it as practice can illuminate a great deal of the questions of early Soviet culture, as well as the crisis of the avant-garde project today.

Roman Osminkin

putinish hickey (excerpts)

I believe I am quite well-prepared to answer

your questions.

Plato, Symposium

[sung]

white night

was grey as ash

and that’s no metaphor

but a meta-form of evil

[…]

2.

whereever you go

look and squint

squeeze in good time

horror in the mouth

all squeezed?

put on the epaulets

cut your coupons

for margarine cheap tobacco

reveries bittering

just as soon as I

got used to the syllogism

of those who have so much

just try touching us

we’ll start kicking as a steed

steam from the nostrils

that Afghan–Iraqi–Libyan tan

days meaner

than a poppyseed stick

little kid with a dose

in his little damp palm

break the bottle jagged

for the enemy’s ugly mug

god is nobody’s

not stingy with rays

squeezed in the buttocks

of the Basmannaya judges

nobody needs you fella

no jerk-offs here

sit straight

repeat after Adorno

felching frictions

with the shaggy tongue

of negation

[...]

5.

big mouths say

enough tragedies

big mouths say

it hasn’t all been eaten yet

big mouths say

the system is in danger

big mouths say

give us time

big mouths say

make tracks

big mouths say

[unclear]

***

/a teeny bit paternalistic/

you can’t outlaw living

pretend to be rags

every baddie

osculates the motherland

in the solar plexus

a putinish hickey

on the generation’s forehead

[and Aristophanes will be the first to slip away

and then

when it has dawned for real

Agatho will meet his maker too]

In a collaborative article, “Sergei Tretiakov’s Chinese journey (The poetic capture of reality on the way to Literature of the Fact),” Alexei Kossykh and Pavel Arsenev discuss the poetic capture of reality as a facet of modernist poetics. The article is dedicated to the early period of Sergei Tretiakov’s literary life, between his early Futurist manifestations and subsequent “red” turn to LEF. During the Russian Revolution and Civil War, Tretiakov lived and worked in the Russian Far East. In 1920 he managed to escape the Japanese occupation of Vladivostok and illegally came to China, where in 1921 hе wrote the poem “The Night. Peking” — a poetic response to his first arrival in exotic China. The distinctive feature of the poem is its lexicon, which includes a great number of neologisms (depicting acoustical, olfactory, and visual sensations). Each metaphor refers to some exotic feature of Peking — its smell (Chinese street cuisine), its soundscape (the sounds and calls of Peking merchants and peddlers, Peking opera and street music), and its visual images (the architecture of Old Peking with its night lanterns). Tretiakov strives to recreate the missing link between language and the world through typically modernist devices of onomatopoeia and neologism. However, while Tretiakov engaged with his first trip to Peking poetically, this approach would soon seem inadequate to the future advocate of Literature of the Fact. All of this same material would be opened up from entirely different methodological positions after Tretiakov began to move away — in a most radical yet consistent manner — from the cultivated spontaneity of his perceptions to the primacy of the thing not yet put into words.

In “The Medvedkin-Bruegel effect,” Andrei Fomenko examines Aleksandr Medvedkin’s film Schaste [Happiness] — which combines political satire and surrealist fantasies on Russian folk themes — as one of the first attempts towards a conscious and methodical laying-bare of the conventionality of cinematic language. The term “montage of attractions” in application to Medvedkin’s method reveals that Medvedkin’s attractions, unlike Eisenstein’s, do not so much persuade as pull the viewer in with their fairylike ingenuity. In his radical experiments, Eisenstein sought to bring cinema closer to text, to formulate abstract ideas using film shots, transforming the image into an utterance. Medvedkin, on the contrary, takes up the formula of “everyday wisdom” — where the signifier is maximally transparent and, as it were, dissolved into the signified — and through its medial transformation makes the signifier visible, palpable and active (as Daniil Kharms put it, “if I throw this word out the window, the glass will break”). In this way, Medvedkin nullifies the results of efforts towards “securing” signifiers and brings us back to the starting point, where the thing is already a sign. Despite Chris Marker’s designation, Medvedkin was — in art, at any rate — not a Bolshevik, but an anarchist.

The “texture” of Medvedkin’s images, while not completely obscuring the incriminatory significance of a given scene, nevertheless does make it more vague (such is the scene with the soldiers ordered to arrest the protagonist for his unauthorized attempt to die — itself a literalization of the expression “to [not] let someone die in peace”). Fomenko finds an analogous strategy in a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, “Netherlandish proverbs:” the figures in the painting illustrate the literal meaning of deadened figures of speech and thereby embody the “madness of an image” no longer subjugated to the wisdom and edification of language.

This issue also contains a first-ever translation into Russian of “Utopian Miniature: The conductorless orchestra,” a chapter from Richard Stites’ Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution, as well as translations from the poetry of Victor Segre, who belonged to the Russian revolutionary-democratic tradition but wrote in French and in the context of French literature (particularly avant-garde).

In “The emergence of the Soviet subject: colonizing the colonizers,” Ilya Kalinin examines the discursive mechanisms at work in the formation of the Soviet subject. Kalinin employs postcolonial theory as his basic analytical framework, with its propensity for problematizing the rift between the individual in the process of liberation and the language through which his subjectivisation takes place. As it was built into the previous socio-economic practices and coordinates of cultural hegemony, this language gives the new subject the possibility of independently achieving political and cultural representation; however, it also places him under command of the system of domination and subjugation that remains embedded in the language he has inherited. Various approaches to the solution of the problem of representation (in both the political and symbolic sense) helps to reveal a theoretical horizon relevant both to the Soviet cultural revolution of the late 1920s-early 1930s and to the Western intellectual context and reactions to social unrest in the late 1960s.

This issue also includes excerpts from Oleg Kireev’s book (currently being prepared for publication) “Earth. The 50’s” and a review by Sergei Zavialov of a collection of poems by poets who participated in the Second World War, “The tram is going to the front” (Free Marxist Publishing, 2011).